Chapter 5

The Bar Exam, Revisited

The Fall and Winter of 1970-71 was like a blur. I took two bar review courses and studied day and night. At work, I tried not to let my study schedule interfere with the needs of the department and my crew. But almost every other waking minute was committed to studying. Every day off, including weekends, I could be found at the LA County Law Library.

Almost daily, while studying, a succession of legal concepts or the logical bases of appellate court rulings would emerge like bright lights from the fog of esoteric language and boring details that I was immersed in. Frequently, I'd say to myself, "How could I have not understood that prior to now?" Or, "No wonder I flunked the exam!" I was satisfying that jealous mistress (the law) and she was rewarding me.

At the same time, my family was not getting the time and attention they deserved. My wife increasingly was frustrated with bearing the responsibility for the boys all by herself. At the time, it seemed to me that she was saving up complaints and crises to dump on me when I came home to sleep, shower and change clothes. I'm sure it seemed to her that she'd been playing second fiddle to the law and the fire department for a long, long time.

Tom and Andy were doing average work in school but my stepson had always suffered from a learning deficit and retarded social skills. These problems seemed to magnify in junior high school and high school. Often, while studying for the bar exam, thoughts of my family and the responsibilities I was avoiding would crowd in on me, and my head and face would feel a hot rush of anxiety. But then, forcing myself to concentrate on that single-minded goal, I would sweep all else from my mind.

I don't even remember taking the oral interview for the Battalion Chief exam. It happened sometime in the latter half of 1970 and I have a record that says I scored a "100" on that part of the process. The Appraisal of Promotability score was a "90." For a day or two, I probably worried about why I didn't get a higher score on the AP, but I couldn't let it distract me. When the eligibility list came out I was number 5. That was the lowest position I'd ever held on a promotional list, but it also meant I would become a Battalion Chief sometime in 1971, fourteen years after Captain Richie Lawrence first taught me how to loop a hydrant.

Finally, as the day of the bar exam approached, I decided to stay in a motel near Glendale the night before the exam, and the nights of the first two days of the exam. We couldn't afford it, and my wife was angered that I would choose to stay away from my family. But I knew that the crisis atmosphere at home would distract me from the exam.

Law professor Beverly Rubins presented one of the bar review courses I had taken. She had analyzed bar exam questions over a period of many years and would concentrate her bar review courses on those questions or issues that were most likely to appear on the next exam. By the end of the first day of my second exam, I looked up to the Spanish-style balconies surrounding the big testing room in the Glendale Civic Auditorium. I expected to see Beverly Rubins on one of those balconies, taking a bow. Her predictions were uncanny and I was feeling confident.

At the end of the third day, walking to the parking lot, I encountered one of my fellow graduates from Southwestern University. "How did you do?" he asked. "I aced it!" I replied, surprising both of us with my confidence and candor (that supposedly can become a jinx). I had actually enjoyed the exam -- because I was so well prepared. Something inside me was shouting that I had become a lawyer, that the biggest intellectual challenge of my life was behind me, and that I could now start picking up the pieces of my life. I felt as though I had been freed from captivity. On the way home, I rolled down the car windows, turned the radio up loud, and sang along with the music.

In the next several weeks, I

discovered a syndrome familiar to generations of military

personnel. When you return from a long war, you learn that the

people you left at home have adjusted to your absence. In fact,

in some respects, they enjoy their self-sufficiency. The

returning warrior wants to get things back in shape right away.

His family probably won't welcome many of the changes he wants to

impose.

At work, in the evenings between calls, I watched TV and played cards with the crew. I helped a couple of younger members design study programs for future promotional exams, and I finished the manuscript for my fire company supervision textbook which, by this time, had been titled, "Effective Company Command."

As Luck Would Have it

In late April, I sent the manuscript to Dick Friend, who was our department's public information officer. At the time, the department had a rule (probably unconstitutional) that required members to get approval before submitting any materials for publication. I was inclined to challenge the rule but then thought it better to comply.

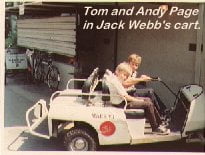

On May 11, 1971, I was on duty at Station 7. Unbeknownst to me, TV producer Jack Webb met that day with executives from NBC. Webb was proposing a new television series based on rescue. NBC agreed to purchase a two-hour special that could possibly spin off a weekly series. Within an hour, Webb was meeting with Robert A. Cinader, one of his executive producers. With orders to research the concept, Cinader walked from Webb's office to his own, across the lot at Universal studios. He was thinking, "Who does rescue?"

It occurred to Bob Cinader that fire departments are the primary providers of rescue services. As he walked into his office, he told Jane Kent, his secretary, to get the fire department on the phone. She called the information operator. Most likely, considering the location of Universal Studios, the operator gave her the number for the Los Angeles City Fire Department.

There are two versions of what

happened next. One version, told to me by a retired LA City Fire

Department chief officer, contends that Jane Kent got a

bureaucratic run-around when she called the City department.

Supposedly, she somehow knew enough to try another fire

department and got in contact with the County Fire Department.

The other version of the story has the information operator

giving Jane the "wrong" number (the County's) in the

first place.

Regardless how it happened, the call went to Dick Friend. Bob Cinader told Dick that he needed someone to do some research and writing for a proposed TV special. My book manuscript was sitting on Dick Friend's desk. There may have been others he could have recommended, but Dick told Mr. Cinader that I was a writer with extensive experience in rescue, and that I was on duty at a fire station in West Hollywood. Then Dick called Station 7 to let me know I might be hearing from someone in the Jack Webb organization.

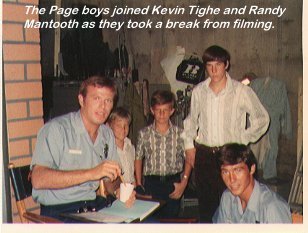

What happened next is detailed in the

"Emergency! Companion." Again, a benevolent bolt of

lightning had struck me. I shared the news with my wife and kids.

The kids were excited about Dad's new connection with Hollywood,

even though none of us knew where it might lead. My wife, on the

other hand, was not very happy about it. I think she saw this as

another competitor for my time and attention.

What happened next is detailed in the

"Emergency! Companion." Again, a benevolent bolt of

lightning had struck me. I shared the news with my wife and kids.

The kids were excited about Dad's new connection with Hollywood,

even though none of us knew where it might lead. My wife, on the

other hand, was not very happy about it. I think she saw this as

another competitor for my time and attention.

In June 1971, I received word that I had passed the bar exam. In the several weeks before getting the exam results, my confidence had wavered a little. I caught myself wondering what I would do if I failed again. I doubted that I had the resolve to endure another marathon of studying. I worried about the stress it would bring to my marriage and family. I knew that I would have to abandon my work with Bob Cinader on the TV special if I studied for the next bar exam. With the letter of congratulations from the State Bar, all those anxious concerns faded away.

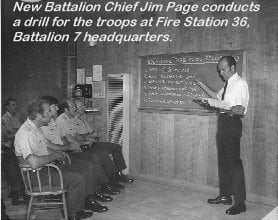

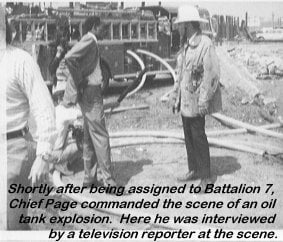

Within a five-day period in July 1971, I

was promoted to Battalion Chief and formally admitted to the

California Bar. In another stroke of good luck, I was assigned to

Battalion 7 on the "B" platoon. Battalion 7 was a giant

area -- about 60 square miles stretching from South LA to the

southerly tip of the Palos Verdes Peninsula. At the time, the

battalion consisted of 13 fire stations housing 13 engine

(pumper) and two truck (ladder) companies. Within the area were

several major refineries and chemical plants, hundreds of large

warehouse and manufacturing facilities, thousands of small

businesses, and about a half-million people.

Within a five-day period in July 1971, I

was promoted to Battalion Chief and formally admitted to the

California Bar. In another stroke of good luck, I was assigned to

Battalion 7 on the "B" platoon. Battalion 7 was a giant

area -- about 60 square miles stretching from South LA to the

southerly tip of the Palos Verdes Peninsula. At the time, the

battalion consisted of 13 fire stations housing 13 engine

(pumper) and two truck (ladder) companies. Within the area were

several major refineries and chemical plants, hundreds of large

warehouse and manufacturing facilities, thousands of small

businesses, and about a half-million people. Battalion 7 always had been the site of

lots of action, and a Battalion Chief assignment there was

prestigious.

Battalion 7 always had been the site of

lots of action, and a Battalion Chief assignment there was

prestigious.

Of special interest to me was the fact that Battalion 7 was the center of our paramedic program -- which had evolved from the so-called "Rescue Heart Unit." I saw this new program as the key to our department's future and I wanted to learn as much about it as possible.

At the time, every Battalion Chief on a field assignment in our fire department had a chief's aide (driver). From the start of my assignment, every time an extra paramedic was on duty, I would assign him as my aide. My goal was to learn as much as I could from them. At one time or another each of the original six LA County paramedics worked at least one shift with me. They seemed pleased to have a chief who was interested in them.

The pioneer paramedics all told me that they felt their program was in jeopardy. There was no single person in the fire department that had responsibility and authority for the growth and expansion of the program. In fact, Richard Houts, the chief of the department, openly referred to the program as "temporary" or "an experiment." Other chiefs, taking their cue from the top boss, treated the paramedic program as a temporary stepchild.

In the absence of assertive leadership from the fire department, County Supervisor Hahn arranged for the appointment of a retired Army Lieutenant Colonel as the administrator of the program. By the time I arrived in Battalion 7, "the kernel," as the paramedics called him, had already made some tactical errors. Initially treating the firefighter-paramedics as though they were enlisted foot soldiers had produced a rebellious response. I perceived the need to step in the breach and serve as a buffer between the warring parties.

Other problems included supply and maintenance. The County's mechanical repair shops were notoriously slow and inefficient. Replacement of front brake linings on a rescue truck could take four to five weeks -- and then the truck might be returned to service with defective repairs. Reserve rescue trucks were in short supply and it was not uncommon for stations 59 or 36 (the two stations with paramedics in Battalion 7) to be using a reserve sedan or station wagon as a rescue vehicle.

Because the program was so new, conflicts between the paramedics and nurses and physicians -- both on the street and in hospitals -- was almost a daily occurrence. Most medical personnel simply had not heard of paramedics, knew nothing of their training or capabilities and, as often as not, were shocked to see firefighters taking blood pressures, starting IVs, hooking up patients to cardiac monitors, and carrying portable defibrillators.

Conflict with fire department Captains and Battalion Chiefs also occurred on a regular basis. Some of the more senior fire department officers didn't adjust easily to the new program. Especially difficult for them was accepting that a young firefighter/paramedic at a medical emergency scene could have superior authority over patient care.

In order to keep their units stocked and re-stocked, and in order to take advantage of continuing education opportunities at their base hospital, the paramedics needed the liberty to leave their stations and function for long periods without the direct supervision of a company officer. This was a dramatic break with tradition and many officers, up to and including the department's second-highest ranking chief, complained continuously that the paramedics were "out of control."

The third group of trainees was about mid-way through the paramedic course when I arrived in Battalion 7. They were to be assigned on Squad 209 at Station 9 in the Florence-Graham area, in another battalion. But numerous important details were awaiting decisions or action from the fire department's headquarters. For example, ordering patient care equipment for the rescue squad vehicle, developing a contract between the department and St. Francis Hospital (which was to be the base for Squad 209), and arranging for radio linkages that would allow contact between the squad and the hospital.

Before long, I was free-lancing, operating outside the boundaries of my job description, and trying to cure all the problems that had come to my attention. Almost daily, I was stepping into situations without permission, breaching the chain of command to make things happen. For a probationary Battalion Chief, it was high-risk behavior, but I was compelled to be an advocate for the paramedics. I was driven to make sure my fire department didn't lose or reject the key to its future.

My direct boss was Division Assistant Chief Paul Schneider, a tall thin man about 15 years my senior. Chief Schneider was soft-spoken and seemed uncomfortable in interpersonal situations. He was also enthusiastic about the paramedic program, but his intense loyalty to the fire department and a sense of protocol and decorum that was reflective of his generation prevented him from forcing issues and embarrassing the higher-ups.

I knew I was making Chief Schneider uncomfortable with my advocacy for the paramedic program. Also, I knew he was catching flack from on high about my failure or refusal to stay within the chain of command. The department's deputy chief, in particular, was complaining to others about me, often stating that "Chief Page is out of control." But he didn't have the guts to say anything to my face, to put his complaints in writing, or to instruct Chief Schneider to reel me in.

Many years later, I still felt badly about the distress I caused Chief Schneider. He was a fine gentleman with great integrity. He was a very capable firefighter, as was his father before him. Almost single-handed, Paul Schneider guided the incorporation of the City of Carson (which kept that highly industrialized community as a part of the County fire protection system and out of the financial grips of the cities of Los Angeles or Long Beach). Every day in 1971-72, I wrestled with the need to make the paramedic program work versus the desire to please my boss.

My research work for the Jack Webb organization was completed and I was waiting for further word on whether the proposed TV special would materialize. As soon as I was admitted to the bar, I received an invitation from a friend to work as a part-time associate in his law firm in Covina, a suburb about 20 miles east of Los Angeles and about 10 miles from my home in Hacienda Heights. To get me started, he turned over several of his cases to me. Also, I began to receive calls from firefighters who needed a lawyer for one reason or another.

Within a few weeks, it was clear to my wife

that her dream of greater balance -- between work, marriage,

family and leisure -- was not to be. If I wasn't on duty at the

fire department, I was coordinating the paramedic program off

duty, or I was at the law office. To me, all my career dreams

were being realized but I was nagged by a combination of guilt

and anger at home.

Within a few weeks, it was clear to my wife

that her dream of greater balance -- between work, marriage,

family and leisure -- was not to be. If I wasn't on duty at the

fire department, I was coordinating the paramedic program off

duty, or I was at the law office. To me, all my career dreams

were being realized but I was nagged by a combination of guilt

and anger at home.

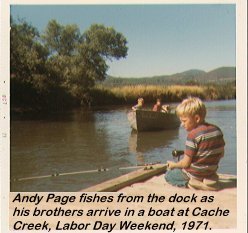

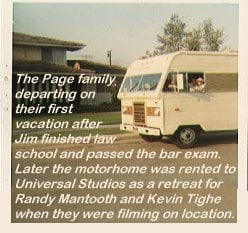

For the first time in years, we had some

extra money. I bought a Champion motorhome and we took a vacation

trip in it to Clear Lake in Northern California. It was great fun

with the kids, fishing and swimming and boating, campfires and

roasting marshmallows, watching shooting stars in the night sky.

For the first time in years, we had some

extra money. I bought a Champion motorhome and we took a vacation

trip in it to Clear Lake in Northern California. It was great fun

with the kids, fishing and swimming and boating, campfires and

roasting marshmallows, watching shooting stars in the night sky.

Within days of that family vacation, Bob Cinader received the okay to proceed with the television special, which was to be named "Emergency!" Thus began another drain on my time and energy. However, I didn't see it that way. On top of my job (which I loved), and my law practice (which I enjoyed), I was to have an influential role in shaping a television special which could share our paramedic program with the world. I recognized that as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Once again, my involvement in planning and creating the World Premiere special and the subsequent television series is detailed in "The Emergency! Companion." Not mentioned in that account is the continuing stress that my multiple activities imposed on my marriage.

Another event not mentioned in the "Companion" was Jerry Stanley's heart attack. Jerome Stanley was a 51-year old executive of the NBC broadcast standards department. In other words, he was a censor. Firefighter Don Pierpont was my aide and, on a day in early 1972, we drove the Battalion 7 car to Universal to view the "dailies." At the time, the projection rooms were in a building on the Universal lot. Since we were on call for emergencies, Don parked the fire department sedan next to the projection building.

There were six to eight rows of upholstered seats in each projection room. In the center was a console with a telephone and a small light. The producer, director and editor usually would sit in the seats around the console. When the dailies for "Emergency!" were projected, Bob Cinader was always next to the console and clearly in charge. He seldom had anything good to say about the footage he was viewing and, depending on his mood, he could be downright abusive to those around him. On the day in question, he was in a bad mood.

All of a sudden, the rear door of the projection room opened, allowing daylight to hit the screen. "Close the goddam door!" Mr. Cinader bellowed. In response, a man's voice timidly asked if there was a "fireman" in the room. Upon hearing that, Don Pierpont and I jumped to our feet and headed to the door. When he saw us, the man said someone was having a heart attack in the projection room next door.

When we arrived in the next-door projection room, a middle-aged man was indeed exhibiting all the signs of a myocardial infarction. He had gray hair and was wearing a white dress shirt with a tie, which had been loosened at the neck. He was grimacing with pain and sweating profusely. He complained of feeling very weak. A studio nurse had arrived before we did and she was trying to hook up her portable oxygen equipment (which she was unfamiliar with).

Don was not yet a paramedic but he had worked with the paramedics on many heart attack incidents and he knew what to do. As he unbuttoned Mr. Stanley's shirt and lay him down on the floor, I picked up the phone and asked the studio operator to connect me with the County fire department's emergency number (9-1-1 had not yet been adopted). As Don grabbed the oxygen equipment away from the studio nurse and started to assemble it, I asked the dispatcher to respond Squad 7 (recently upgraded to paramedic capability) to the projection building at Universal Studios. I checked my watch. It would be a long response for Squad 7 and I wanted to keep track of the time.

As the studio nurse heard me call for the paramedics, she objected. "An ambulance has already been called," she said. We knew it would be a private ambulance with marginally trained personnel. "That's alright," I told her. "Our paramedics will help them when they get here." Meanwhile, Don was administering a steady flow of oxygen to our patient and his color was improving.

We were in a race against time. If our patient slipped into ventricular fibrillation before the paramedics got there, we would immediately start CPR. But we knew that the chances of survival would drop off rapidly with each minute after he lapsed into V-fib - if that were to happen. It occurred to me that the paramedics would need to make base hospital contact before starting any advanced procedures. That's the way things were in the early days. It occurred to me that their radio would never reach their base hospital from inside a projection booth at Universal Studios.

I picked up the phone again and waited for the studio operator to come on the line. As I waited, I looked around the room. Several people were watching the event unfold, including Bob Cinader. His composure and disposition had changed completely. He was quiet and studious, absorbing all the nuances of a real emergency. Everybody in the room, including Mr. Cinader, seemed to realize that Jerry Stanley's life was on the line.

The studio operator came on the line. I told her that I wanted the line protected until further notice, and that we were attending to a serious medical emergency. I explained that paramedics would be using the line to transmit an electrocardiogram to a hospital, and that she was not to allow anyone to break into the line. Next I asked her to connect me with the emergency department at UCLA medical center.

While I was waiting for the connection, Don Pierpont told the private ambulance guys that we were going to keep the patient in his position until the paramedics arrived. The ambulance personnel were young and seemed overwhelmed by their surroundings. They nodded in unison as Don told them the plan. The studio nurse, however, was still flustered and visibly distressed by our take-over of her rescue attempt. She said she thought the patient should be taken to the hospital immediately. I picked up my portable radio and asked Squad 7 for an ETA (estimated time of arrival). "Less than five minutes," was the reply.

Finally, a nurse in the emergency room at UCLA came on the phone line. I tried to explain to her the situation. She didn't understand. UCLA had been a paramedic base hospital only a few weeks and not everyone there was familiar with paramedics and what they could do. Again, I tried to explain the situation, going a little slower and providing more details the second time. She said she wanted to ask someone what to do. "Don't hang up and don't put me on 'hold,'" I said abruptly before she left the phone.

Don continued to administer oxygen to the patient and the ambulance guys were standing nearby, watching. To give them something to do, he told them his supply was running low and asked them to bring theirs in. They looked relieved that there was something they could do and the ambulance guys disappeared outside. Meanwhile, Squad 7 arrived and two blue-shirted paramedics came into the projection room carrying their array of equipment and supplies. The feeling of relief in the room was palpable.

About the time the paramedics arrived I was able to get a knowledgeable person on the phone at UCLA. She understood what I wanted and agreed to stand by for the paramedics to come on the line.

Jerry Stanley finally was moved to the ambulance, with an IV running and morphine sulfate on board to quell the severe chest pain. As soon as he was placed in the ambulance, he lapsed into V-fib. The paramedics defibrillated and a normal sinus rhythm was restored. One paramedic went with the patient in the ambulance to St. Joseph's Hospital in Burbank. The other paramedic drove the Squad 7 truck behind the ambulance.

It was necessary to defibrillate the patient twice again during the ride to the hospital. Throughout that night, the coronary care unit staff defibrillated Mr. Stanley several times before they could stabilize his heart rhythm. The next day, he underwent open-heart surgery for bypass grafts. In 1972, that procedure still was fairly rare and very risky. However, Jerry Stanley survived and went back to work as an NBC censor.

I had seen and heard enough about Hollywood

to know that there were some big risks. Then and now, the

entertainment business can be ruthless, especially to those who

depend on it. I resolved that I would not sell out my fire

department or my career to all the powerful enticements of

Universal Studios, Jack Webb or Bob Cinader. I knew that I would

have clout only as long as they needed something that I could

deliver. I planned to enjoy my status as the fire department's

technical consultant as long as it lasted and then walk away from

it all on my own terms.

I had seen and heard enough about Hollywood

to know that there were some big risks. Then and now, the

entertainment business can be ruthless, especially to those who

depend on it. I resolved that I would not sell out my fire

department or my career to all the powerful enticements of

Universal Studios, Jack Webb or Bob Cinader. I knew that I would

have clout only as long as they needed something that I could

deliver. I planned to enjoy my status as the fire department's

technical consultant as long as it lasted and then walk away from

it all on my own terms.

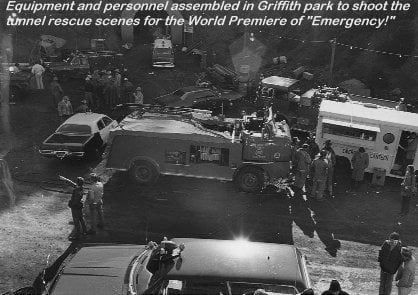

It was pretty clear why I was valuable to

Bob Cinader and the series. From the beginning, working with Dick

Friend, I was able to arrange for large numbers of fire apparatus

and equipment for filming the World Premiere and subsequent

one-hour episodes. I was able to convince on-duty crews to

perform multi-company "drills" that were filmed and

used as stock footage or in specific episodes. Whenever Mr.

Cinader called me for access to some fire department equipment or

facilities, I did my best to open doors for him (sometimes

walking the very thin line between appropriate and

inappropriate).

It was pretty clear why I was valuable to

Bob Cinader and the series. From the beginning, working with Dick

Friend, I was able to arrange for large numbers of fire apparatus

and equipment for filming the World Premiere and subsequent

one-hour episodes. I was able to convince on-duty crews to

perform multi-company "drills" that were filmed and

used as stock footage or in specific episodes. Whenever Mr.

Cinader called me for access to some fire department equipment or

facilities, I did my best to open doors for him (sometimes

walking the very thin line between appropriate and

inappropriate).

Generous access to the fire department and

its personnel gave the series a rich quality of realism. That

wouldn't have been possible if the studio had been renting the

fire engines and paying actors to play the roles of firefighters.

Even though Dick Friend and I skirted the boundaries of propriety

to achieve this result, we rationalized it on the basis of public

education. From the start, we felt that public exposure of our

paramedic program through entertainment television would have a

powerful influence on emergency services throughout the country.

We sometimes talked about how many lives could be saved if

"Emergency!" caused communities from coast to coast to

train their rescuers as paramedics.

Generous access to the fire department and

its personnel gave the series a rich quality of realism. That

wouldn't have been possible if the studio had been renting the

fire engines and paying actors to play the roles of firefighters.

Even though Dick Friend and I skirted the boundaries of propriety

to achieve this result, we rationalized it on the basis of public

education. From the start, we felt that public exposure of our

paramedic program through entertainment television would have a

powerful influence on emergency services throughout the country.

We sometimes talked about how many lives could be saved if

"Emergency!" caused communities from coast to coast to

train their rescuers as paramedics.

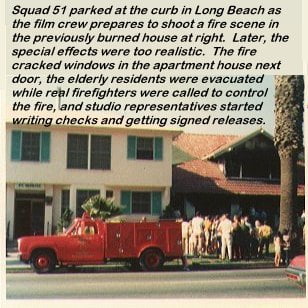

Usually, when making special arrangements to use fire department resources for filming of "Emergency!" I would just do it and then wait for the repercussions. Technically, all such arrangements should have gone through channels. But there were three levels of management between the fire chief and me. Requests for anything out-of-the-ordinary could take months to resolve. Furthermore, the deputy chief was openly hostile to our relationship with the TV series. I knew that he would just sit on formal requests till it was too late. At least once a week for nearly two years, I was scolded for not following the chain of command.

Though I don't remember the date, I'll

always consider a particular incident to be the peak of my

influence. Don Pierpont and I were at the studio, watching the

final version of one of the weekly shows. For some reason, I had

not seen the dailies for this episode, so I was viewing much of

the footage for the first time. The final scene occurred in the

kitchen of Station 51. An attractive young woman was preparing to

leave through the side door. As the camera scanned the crew and

did brief close-ups, each of them was leering at the girl as if

undressing her with their eyes. I felt that the scene reflected

badly on our department and on firefighters generally, and I

demanded that it be re-shot (an extremely expensive process). The

next day, cast and crew were reassembled and the scene was

re-shot.

Though I don't remember the date, I'll

always consider a particular incident to be the peak of my

influence. Don Pierpont and I were at the studio, watching the

final version of one of the weekly shows. For some reason, I had

not seen the dailies for this episode, so I was viewing much of

the footage for the first time. The final scene occurred in the

kitchen of Station 51. An attractive young woman was preparing to

leave through the side door. As the camera scanned the crew and

did brief close-ups, each of them was leering at the girl as if

undressing her with their eyes. I felt that the scene reflected

badly on our department and on firefighters generally, and I

demanded that it be re-shot (an extremely expensive process). The

next day, cast and crew were reassembled and the scene was

re-shot.

For awhile, my status included social engagements, such as dinner with Bob and Jean Cinader, and Steve Downing (Michael Donovan) and his wife. Also, there was a "wrap party" at Universal after the World Premiere was finished, and the 1971 Christmas party -- also at the studio. I took my wife to those parties and she was visibly unhappy at both events. I believe she saw my commitments to the development of "Emergency!" as another jealous mistress, so to speak.

At the Christmas party, my wife had some harsh words for Mrs. Lew Wasserman, wife of the president of MCA Universal. They were spoken loud enough for Mrs. Wasserman to hear. The outburst was uncalled for. I should have recognized the source of the problem and fixed it. But Hollywood had me in its grasp. My reputation at the studio had become more important to me than my family. In the following 14 months, my marriage unraveled and we finally separated.

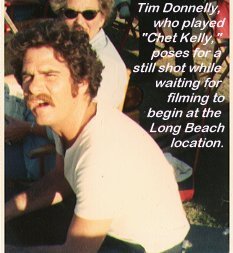

As reported in "The Emergency! Companion," Dick Hammer played the role of 51's Captain through the ninth episode of the series. But the long hours of filming a regular weekly series soon interfered with his family life and career obligations, so he resigned from the show. An actor with the stage name of John Smith was selected to replace him. Smith was an experienced actor, having played in one or more long running Western adventure series. But it seemed that he owed money to almost everybody in Hollywood. As soon as he was hired for the "Emergency!" series, bill collectors and process servers descended on Bob Cinader's office, each trying to get first dibs on John Smith's paycheck. Cinader solved the problem by firing Smith.

By coincidence, I was at the studio viewing "dailies" on the day this occurred. Cinader went into one of his tirades (this time Dick Hammer and John Smith were the subjects). "I need somebody I can depend on," he shouted. Then, quite suddenly, he turned to me and asked, "Do you want to be the fire captain on this show?" In that instant, a million details flashed before me. In what was probably less than two seconds, I processed all my other time commitments, family and professional obligations, and the probable reaction of my wife and the fire chief if I were to become a professional actor. "No, thanks," I said, knowing that I would spend the rest of my life asking myself, "What if…"

Shortly thereafter, Bob Cinader began to develop a close personal relationship with fire chief Dick Houts. Eventually, this friendship included invitations for Dick and Audrey Houts to join Bob and Jean Cinader for weekend sailing on their 32-foot Catalina. The two couples also traveled on foreign cruises together. As the relationship between these two powerful men got stronger, I could feel my clout diminish.

During early 1972 I continued to coordinate the paramedic program from my position in Battalion 7. The program was reaching a crisis point. The original money that had been appropriated for training paramedics and purchasing their equipment was running out. The number of lives saved was growing each month but the fire chief continued to make pessimistic comments about the future of the program. It was clear that he would not take any political risks to seek continued funding.

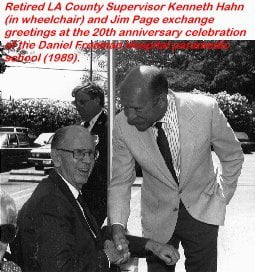

Again, it was Kenny Hahn who came to the

rescue. County government supposedly was in financial distress,

but Hahn and his fellow Supervisors came up with $672,000 to

continue the paramedic program. About the same time, my name

showed up on a transfer list. I was being transferred to LA

Headquarters (Klinger Center), to be in charge of the

Communications and Automotive division.

Again, it was Kenny Hahn who came to the

rescue. County government supposedly was in financial distress,

but Hahn and his fellow Supervisors came up with $672,000 to

continue the paramedic program. About the same time, my name

showed up on a transfer list. I was being transferred to LA

Headquarters (Klinger Center), to be in charge of the

Communications and Automotive division.

I knew what was behind it. The deputy chief was tired of me breaching the chain of command on behalf of the paramedic program. I was serving on numerous committees -- with the LA County Heart Association, the LA County Medical Association, and the County's Emergency Medical Care Committee -- in connection with the evolving emergency medical services (EMS) system. I was giving several speeches each week to civic groups, medical societies and service clubs throughout the county, all to explain what paramedics were and how the system worked.

The deputy chief didn't like my high profile and he let me know it. He wanted to clip my wings. The office job at LA Headquarters would keep me under control -- theoretically. The job of coordinating the paramedic program was given to Battalion Chief Jack Hinton in the Operations Division, located across the hall from my new office at Headquarters.

Jack Hinton was a firefighter's firefighter and a genuinely nice guy, but he was the first to admit he didn't even know how to spell "paramedic." From the first day of my new assignment, Jack was beating a path across the hallway to my office, seeking help. The new money was used to create a second paramedic training center. Starting as soon as possible, and continuing for as long as three years, the department was to convert two additional rescue units to paramedic status every five weeks. It was an ominous task under the best of conditions; it would be impossible without a full-time administrative commitment.

Before long, Hinton was complaining to his boss, Division Chief Ben Matthews. "This is crazy," he would say. "I don't know what the hell I'm doing, and Page is doing his job and mine." Matthews finally went over the head of the deputy chief and explained the situation to Fire Chief Houts. Within days, Hinton was transferred to a field battalion and I was transferred to his job in Operations.

Finally, by July 1972, I was fully authorized to do the job I loved -- building a Countywide paramedic rescue system -- without having to operate outside the chain of command and continually ask for forgiveness. Somewhere in the middle of all the turmoil, I passed my probation as a Battalion Chief.

The headquarters assignment was an eight-to-five job, theoretically. Based on that theory, I tried to continue my law practice during evening hours and on Saturdays. It was a struggle because there were so many nighttime meetings related to the paramedic program. Also, the "Emergency!" World Premiere had evolved into the weekly series and I was scheduling technical assistants, reviewing scripts, and viewing "dailies" (unedited footage from the previous day's filming) and the final version of each episode (before it was sent to the network). My workdays often were 18 hours long.

My mother's family (the Hamiltons) had scheduled a reunion at Howard Prairie Lake, near Medford, Oregon for the summer of '72. We took the motorhome and camped near the shore of the lake. The boys had lots of fun with their cousins, and went fishing with their grandfather (my Dad). We didn't know it at the time, but it would be our last vacation as an intact family.

Copyright 1998, James O. Page