Chapter 6

Conflict

and Controversy

As soon as "Emergency!"

began to appear as a weekly series, the LA County Fire Department

started receiving phone calls and visitors from all over the

country. We hosted fire chiefs and city managers, medical

doctors, public health directors, volunteer ambulance attendants

and citizen activists. Most of them wanted to know if the TV

series accurately portrayed our fire department and its rescue

service. After they saw that it was for real, many of the

visitors wanted to know how they could construct such a system in

their towns.

During 1972 and '73, much of my

on-duty time was spent hosting visitors and answering inquisitive

letters and phone calls. As I went about the business of

coordinating the paramedic program and its expansion, I really

had no time to be a tour guide. So I took the out-of-town

visitors with me almost everywhere I went. At meetings with

hospital administrators, or noontime presentations to service

clubs, or medical-legal lectures for paramedic trainees, or

viewing "dailies" at Universal Studios, I would often

have from one to three guests. They saw it all and heard it all,

including some of the conflict and discord that goes along with

making things happen fast in government.

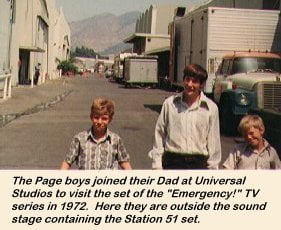

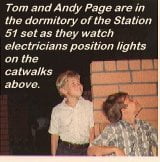

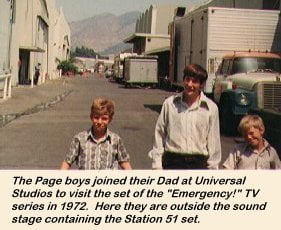

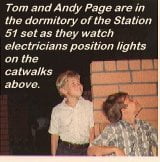

Clearly, the favorite activity for my

tag-along guests was a trip to see "Emergency!" being

filmed, either on location or in a soundstage at Universal.

Clearly, the favorite activity for my

tag-along guests was a trip to see "Emergency!" being

filmed, either on location or in a soundstage at Universal.

Twenty-five years later, I still encounter

people - in places like Rochester, Phoenix, and Kalamazoo -- who

remind me of the day they visited us in Los Angeles and I took

them with me to the studio.

Twenty-five years later, I still encounter

people - in places like Rochester, Phoenix, and Kalamazoo -- who

remind me of the day they visited us in Los Angeles and I took

them with me to the studio.

One of the biggest questions in

the minds of many of our visitors was whether the firefighters in

their towns would be willing or able to be trained as paramedics.

It seemed that in some parts of the country firefighters resisted

any responsibility for medical calls. "We hired on to fight

fires, not handle sick calls," was a commonly heard excuse

in some areas. I had little patience for that kind of attitude

and sent some of my visitors home with a challenge to their local

fire departments.

Also, during 1972, I wrote my

first article for a fire service magazine. The article was

titled, "Why Firefighters?" I submitted it to Dick

Friend's office before sending it to the magazine. Dick sent it

up through channels. Sixty days later, I had heard nothing from

the fire chief's office so I mailed the article to Fire Command

magazine at the National Fire Protection Association. It was

promptly published.

Through "Emergency!" I

had seen and felt the power of the television medium. The article

in Fire Command magazine introduced me to the power of the

printed word. The topic of EMS in the fire service was

controversial at that time and my article was unequivocal.

Throughout the country, those who agreed with me used the article

as a tool of persuading others. Those who disagreed with me saw

the article as dangerous heresy. Without intending to, I had

become one of the more controversial figures in the American fire

service. I wore the mantle with pride, because I knew that the

lives of countless human beings were at stake.

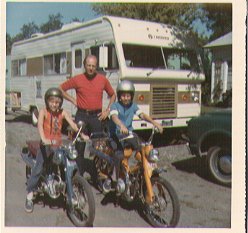

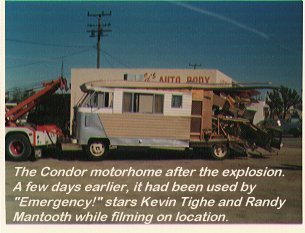

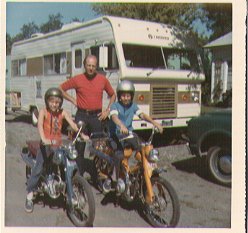

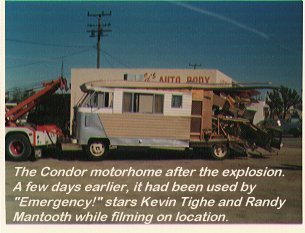

In February 1973, I moved into an apartment

next door to my law office in Covina. On weekends, I would try to

do something with my boys. Meanwhile, I had purchased a second

motorhome, a Condor, which I rented to Universal Studios. It was

used by Randy and Kevin when they were on location. When the

second season of "Emergency!" ended in the summer of

'73, there was a hiatus. I bought dirt bikes for Tom and Andy and

we took a vacation to Washington State in the Champion motorhome

(with the bikes trailered behind it).

In February 1973, I moved into an apartment

next door to my law office in Covina. On weekends, I would try to

do something with my boys. Meanwhile, I had purchased a second

motorhome, a Condor, which I rented to Universal Studios. It was

used by Randy and Kevin when they were on location. When the

second season of "Emergency!" ended in the summer of

'73, there was a hiatus. I bought dirt bikes for Tom and Andy and

we took a vacation to Washington State in the Champion motorhome

(with the bikes trailered behind it).

We traveled to a lake in Eastern

Washington where my family vacationed when I was 12. That was

where I first swam in a lake, operated an outboard motor, went

fishing, camped out under the stars. I had some powerful memories

of that place and I was trying to share them with my sons. It is

said that one can never repeat such an experience. Supposedly, it

all looks different through adult eyes, and that time distorts or

magnifies the memories. That wasn't true in the summer of 1973.

The lake was just as I remembered it, and we had a wonderful

time.

Out of

Clout

Back in LA after the vacation, I

went to a dinner meeting of the Chief Officers Club. That’s

an organization of all chief officers in the LA County Fire

Department. Three or four times a year, they have an event

consisting of golf during the day, and dinner and drinks in the

evening. I didn’t have time to play golf but I usually

attended the dinner. As I recall, the dinner was held at a big

restaurant in the suburban community of Downey. After dinner,

most everybody gathered in the bar for drinks. One by one, they

left for home until the last two remaining chiefs were Fire Chief

Richard Houts and me.

casino en línea en México.

Several weeks earlier, I had

objected to a scene in one of the "Emergency!" scripts.

I thought it reflected poorly on our personnel. My objections

were ignored. Then, I objected again after the scene had been

filmed. Again, I was ignored. I knew my clout was gone. I wrote a

memo to Chief Houts, thanking him for the opportunity to

represent the department in creation of the series and resigning

from my position as chief technical consultant. He ignored the

memo, sending word back to me through Dick Friend that he had

never appointed me to the position in the first place. That hurt.

At the Chief Officers Club

dinner, Dick Houts had a driver to get him home safely and he was

imbibing more than usual. It was close to midnight and, as we sat

alone at the bar, I took advantage of his condition and asked him

why he seemed so hostile to me. He told me that for a long time,

almost every problem that arrived in his office had my name on

it. "Your name is mud," he said, "and you

shouldn’t bother to take any more promotional exams."

That really hurt.

Sixteen years after Richie

Lawrence first showed me how to loop a hydrant, I had become my

fire chief’s biggest problem. I had thumbed my nose at

organizational politics and the chain of command, and I had

driven my career into a brick wall. For the next several weeks, I

recalled thousands of situations where I’d been faced with

the dilemma: "Should I do what I know must be done and ask

forgiveness later, or should I ask for permission and then make

excuses while waiting for the higher-ups to make a

decision." Finally, I decided I would not have done things

differently.

About that time, I was given

an opportunity to travel to Asheville, North Carolina, and speak

at the annual convention of that state’s Association of

Rescue Squads. I’d never been east of the Mississippi River,

so I arranged to drive a rental car from Asheville up the East

Coast to Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York and Boston

after the convention.

My hosts in Asheville treated

me royally. Everybody was interested in the

"Emergency!" series and the LA County Fire Department.

I spoke at several workshops and then gave the banquet speech at

the Oak Park Inn. Afterwards, a representative of the

Governor’s office approached me. "We have new

legislation and funding to create a statewide emergency medical

services program in all one hundred counties of North

Carolina," he advised. "We’re looking for someone

who can put it all together for us. Would you be

interested?"

Obviously I was flattered,

especially after being told by my chief in LA that I was his

biggest problem. But the thought of leaving my fire department

and moving to the East Coast seemed completely out of the

question. The man persisted. He asked me to spend a day in

Raleigh on my way to Washington. I did, and was intrigued by the

opportunity and grateful for the offer, but declined it.

Back in LA, the daily and

nightly grind continued. I found that my trip back east had

changed me. Most important, I had learned that several other

locales had been educated and inspired by "Emergency!"

and were making some major strides to improve EMS. In Illinois,

North Carolina and Maryland, there was a commitment from the

Governors’ offices. Necessary laws had been passed and money

had been appropriated. I caught myself wondering what it would be

like to build a program without the need to sidestep dinosaurs or

battle with resistant bureaucracies.

The week of October 7th

was typically hectic. I worked a 24-hour overtime shift in

Battalion 5 (Malibu) on Sunday. Monday the 8th

was Columbus Day, an official holiday at fire department

headquarters, but I spent eight hours there catching up with

paperwork. The rest of the week was full of meetings, answering

phone messages, writing memos, and reading reports. On the 9th,

I gave a lecture at St. Mary’s Hospital in Long Beach. On

the 10th, I met with

Heart Association officials to plan a public education campaign.

On the 11th, I

attended an organizational meeting of a new association for

paramedics. On Friday, the 12th,

I spoke at a paramedic graduation ceremony at Harbor General

Hospital. On Tuesday and Thursday nights that week, I met with

clients in my law office.

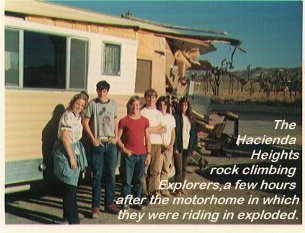

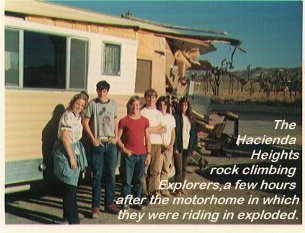

Saturday and Sunday had been

reserved for my step-son. He was 16 and socially immature. He was

active in the swim club but had no close friends. Then he took an

interest in rock climbing and joined an Explorer Post that

specialized in it. There were only about ten kids in the Post,

and they ranged in age from 13 to 17. They wanted to climb rocks

at the Joshua Tree National Monument and I offered to take them

there in the Condor motorhome.

The Condor was bigger and

more comfortable than the Champion motorhome. I had the interior

refurnished and carpeted and Randy Mantooth arranged to have an

eight-track sound system installed in it (that was the

state-of-the-art in 1973). When the Condor wasn’t being used

by the studio, I loaned it to friends and family (and used it

myself when I had the time).

A

Fateful Event

At 5:00am on the morning of

October 13, 1973, we left Hacienda Heights with six Explorers

– three boys and three girls - aboard the Condor, and the

fathers of two of the kids following us in a station wagon. After

about an hour, we stopped to buy some groceries. I planned to fix

breakfast after we got to our destination. Also, I lit the water

heater so we would have hot water when we arrived.

The next hour was uneventful.

The sun was rising from the east and we were driving into it but

the desert air was crystal clear. At about 7:30, the kids were

all in the back of the motorhome. Some were on the rear bunks and

others were sitting on couches. As we approached our destination,

I yelled, "Here it is, you guys." With that, all the

kids ran to the front of the motorhome to look through the

windshield. An instant later, we were enveloped by the pressure

of an explosion.

As the adrenalin rushed

through my body, my senses sharpened and events seemed to occur

in slow motion. I recall seeing a network of cracks appear in the

windshield and then the windshield disappeared, blown outward by

the force of the explosion. In that same instant, I felt a rush

of air and debris fly forward past my right ear. Instinctively, I

was bringing the vehicle to a halt before I could turn to look

over my shoulder. The air was filled with dust and toward the

rear of the motorhome I could see daylight.

Before I could get it to a

complete stop, kids were jumping out of the vehicle, through the

front door. I was trying to count them, expecting that we would

be in the middle of a fireball in the next second. Finally, with

the rig stopped, I rose from the driver’s seat and turned to

look for injured kids. The air was still full of dust but I could

see all the way back to where the rear of the body had blown off.

I couldn’t see any kids so I jumped out the door to get a

head count.

At that point, I saw a sight

that I will never forget. The fathers who had been following us

had seen the full dimensions of the explosion. They knew not the

fates of their children as they abandoned their car and ran

toward us. Their faces were contorted with fear and anguish.

Thirty seconds later, we all knew that we had somehow escaped a

disaster. A 40-pound back-pack that had been on one of the bunks

was found 300 feet away from the motorhome. If the explosion had

occurred while the kids congregated in the back of the vehicle,

several surely would have died.

As it turned out, the only physical

injury was a small scrape on the ankle of one of the girls. The

cause of the explosion was found to be two simultaneous defects.

The thermostat on the water heater failed to shut off the flame

when it reached 140 degrees F. It continued to heat the water

till it reached the boiling point (212 degrees). At that point, a

pop-off valve on the top of the hot water tank should have

released the steam but it failed too. As a result, the water tank

became a steam pressure vessel. When water turns to steam in a

sealed container, it expands about 1,100 to one, creating enough

power to move a locomotive — or demolish a motorhome.

As it turned out, the only physical

injury was a small scrape on the ankle of one of the girls. The

cause of the explosion was found to be two simultaneous defects.

The thermostat on the water heater failed to shut off the flame

when it reached 140 degrees F. It continued to heat the water

till it reached the boiling point (212 degrees). At that point, a

pop-off valve on the top of the hot water tank should have

released the steam but it failed too. As a result, the water tank

became a steam pressure vessel. When water turns to steam in a

sealed container, it expands about 1,100 to one, creating enough

power to move a locomotive — or demolish a motorhome.

After making arrangements to get all

the kids home, and having the motorhome removed to a wrecking

yard in Yucca Valley, I had the rest of the weekend to think. I

thought about the tragedy that almost happened. I thought about

the way I’d been spending my life. I thought about all the

bridges I had burned and the anger (in myself and others) that I

was confronting every day. I realized that I was very unhappy and

that I probably wouldn’t be able to make things better in my

current situation.

After making arrangements to get all

the kids home, and having the motorhome removed to a wrecking

yard in Yucca Valley, I had the rest of the weekend to think. I

thought about the tragedy that almost happened. I thought about

the way I’d been spending my life. I thought about all the

bridges I had burned and the anger (in myself and others) that I

was confronting every day. I realized that I was very unhappy and

that I probably wouldn’t be able to make things better in my

current situation.

On Monday the 15th,

I called North Carolina and told them I’d like to talk some

more about the State EMS Chief’s job. They arranged for me

to fly to Charlotte later in the month for an interview by state

government officials. At the interview, I urged them to contact

Chief Houts and his deputy chief. "They’ll tell you

that I’ve got the energy of three men, that I drive people

crazy with new ideas, that I’m impossible to control, that I

can’t take ‘no’ for an answer, and they’d be

glad to see me go." State Senator F. O’Neil Jones

replied, "We have already talked to them, that’s

exactly what they said, and we’ve decided you’re

exactly the kind of guy we need."

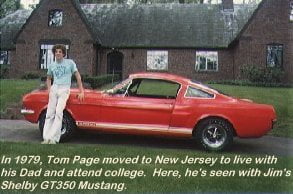

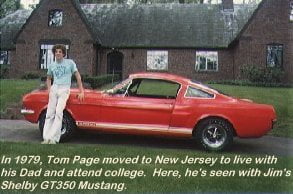

November 30th

was my last day with the LA County Fire Department. On December

10th, I headed east

in my Shelby GT-350 Mustang and arrived in Raleigh on the 16th.

The boys stayed in California with their Mom. We saw each other

six to eight times a year, including summer vacations. My

stepson’s problems multiplied when he discovered marijuana.

He went to live with his father in Florida and served time there

for burglary. When his mother last saw him more than ten years

ago, he was an IV drug user. We haven’t seen or heard from

him since then and we presume he’s dead.

Tom and Andy both have done

well. After high school, each of them moved in with me.

Tom graduated from Ithaca College in

New York with degrees in photography and cinematography. He has

been a commercial photographer in San Diego County for about ten

years. He is married with two children and lives in Vista,

California. Andy is a firefighter/paramedic in Poway (San Diego

area) and is working on his bachelors degree and studying for the

Captain’s exam on his days off. He is married with two kids

and lives in Temecula, California. Tom and Andy are both good

husbands and fathers — better than their Dad was — and

I’m very proud of them. Their mother (Pat) remarried and has

a lovely 22-year-old daughter who is attending UC Santa Barbara.

We include them in all our family get-togethers.

Tom graduated from Ithaca College in

New York with degrees in photography and cinematography. He has

been a commercial photographer in San Diego County for about ten

years. He is married with two children and lives in Vista,

California. Andy is a firefighter/paramedic in Poway (San Diego

area) and is working on his bachelors degree and studying for the

Captain’s exam on his days off. He is married with two kids

and lives in Temecula, California. Tom and Andy are both good

husbands and fathers — better than their Dad was — and

I’m very proud of them. Their mother (Pat) remarried and has

a lovely 22-year-old daughter who is attending UC Santa Barbara.

We include them in all our family get-togethers.

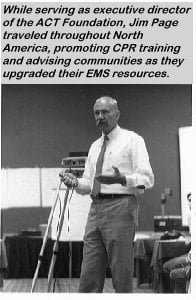

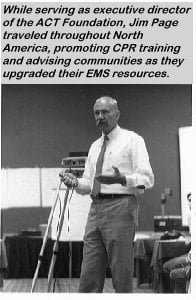

My career took me to Basking Ridge,

New Jersey in 1976, as executive director of the non-profit ACT

(Advanced Coronary Treatment) Foundation. Funded by several

pharmaceutical companies, my job was to promote CPR training

nationwide and to provide technical assistance to communities in

upgrading their EMS to the paramedic level. It was the best job I

will ever have but our success — in promoting CPR and

upgrading EMS — ultimately would bring an end to the

Foundation. In anticipation of that event we created JEMS

(Journal of Emergency Medical Services) in 1980.

My career took me to Basking Ridge,

New Jersey in 1976, as executive director of the non-profit ACT

(Advanced Coronary Treatment) Foundation. Funded by several

pharmaceutical companies, my job was to promote CPR training

nationwide and to provide technical assistance to communities in

upgrading their EMS to the paramedic level. It was the best job I

will ever have but our success — in promoting CPR and

upgrading EMS — ultimately would bring an end to the

Foundation. In anticipation of that event we created JEMS

(Journal of Emergency Medical Services) in 1980.

During those years, I

didn’t have much contact with Bob Cinader. He became a

member of the LA County Paramedic Commission and the newly-formed

(but now defunct) LA County Fire Commission. Occasionally, he

would call me out of the blue and he’d complain at great

length about something that was bugging him. He subscribed to

JEMS and he’d sometimes call in response to something

I’d written in my monthly column, "The Publisher’s

Page."

Then I heard that Bob had

died. In the January ’83 edition of JEMS, I published the

following column, titled "One of the Boys":

"It was May 11,

1971, when my path first crossed that of Robert A. Cinader.

We met at Fire Station 7 in West Hollywood. He offered me a

job, researching potential story material for a proposed

television series. It was a turning point in my life, with

both good and bad consequences.

"Bob Cinader

presented himself in a kind of stoop-shouldered indifference

to physical appearances. More often than not, his facial

expressions were a mix of frowns and scowls. In meeting or

greeting him, one could expect a report on numerous ills,

pains and inconveniences.

"I never knew

very much about his childhood or adolescence in New York. I

presume he was a kid who couldn’t master stickball but

made up for it with his mastery of the written word. Bob

Cinader was brilliant, one of the greatest minds I have ever

encountered. Still, there were many hints that he would

rather have been good at stickball.

"Bob died of

cancer last November. Probably, in his final days, he thought

about his life, its high points and lows. Certainly, his long

marriage to a lovely lady must have ranked high in his life

achievements. But I would guess that the Summer of ’71

also would be classed as one of the man’s fondest

memories. It was during the time that Bob Cinader (possibly

for the first time) became ‘one of the boys.’

"Our early

research had resulted in selling the concept of

‘Emergency!’ to NBC. Bob’s task was to develop

a script for a World Premiere TV movie, although producer

Jack Webb would get most of the credit for it. Already, there

was talk of a weekly series spinning off from the World

Premiere. Bob Cinader would be executive producer of the

one-hour shows and he had just a few weeks to get acquainted

with the world of firefighters and paramedics.

"By that time, I

was a battalion chief in a 60 sq. mi. region of South LA. For

several weeks, Bob Cinader accompanied me on my tours of

duty. At first, in deference to a film producer in their

midst, the firefighters and paramedics were still and polite.

But after a few days they reverted to form. I remember the

first time Cinader got ‘stuck in the tank’ (forced

to wash dishes) after losing a hand of firehouse poker. He

complained, and scowled, but I think he loved being treated

as one of the boys.

"As we traveled

throughout Battalion 7, visiting fire stations and hospitals,

rolling on fires and emergency calls, he became less an

attraction. The real people would greet him with a ‘Hi,

Bob.’ In the back seat of my red sedan, he would talk

endlessly between puffs on his foul smelling cigarillos. My

driver and I heard more than we ever wanted to know about the

Los Angeles Police Department and ‘Adam 12’ (which

he had produced). But as the days passed, his devotion to

paramedics and EMS became a passion that would have no rival

in his remaining years.

"As we all know,

Bob Cinader’s ‘Emergency!’ series became a

huge success. More than 120 one-hour segments were produced

over a six-year period. Some of those segments have been

re-run as many as nine times in the U.S. The show would have

gone on even longer if the principal actors hadn’t tired

of their ‘Johnnie and Roy’ roles.

"Bob

Cinader’s passion for EMS got him appointed to LA

County’s Paramedic Commission. He tended to immerse

himself in the turbulent politics of LA County’s EMS

system. His strong opinions and his dominating style produced

for him as many enemies as friends. There are those who

suggested that he was ill-prepared to design or govern a

health care system.

"Prepared or not,

there have been few people who have had more influence on any

aspect of health care. In his docu-drama approach to

presenting ‘Emergency!’ Bob Cinader elevated

America’s (indeed, the world’s) expectations. No

new concept in health care has spread as rapidly as

prehospital ALS (paramedic) services. One reason is the

public education that was accomplished through an unusual

prime-time TV series.

"He may never

have been good at stickball. But his mind, his talents, and

his dogged persistence produced a message that has profoundly

affected cities and towns throughout North America. Without

Bob Cinader’s TV show, paramedics might have become a

brief experiment in a few locations. Instead, countless lives

have been saved.

"I wish I had

known he was dying. I would have tried to let him know the

importance of his contribution. In the process, I would have

let him know that I liked him best with suds up to his elbows

— stuck in the tank as one of the boys."

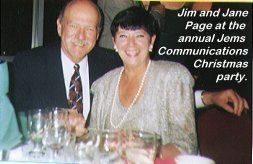

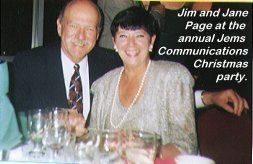

When I went to work for the

ACT Foundation my secretary was an attractive divorcee named Jane

Seymour.She had two daughters about the same ages as my sons.

Jane and I became good friends and

worked well together, although we resisted the temptation to get

romantically involved — until 1980, that is. By 1983, the

ACT Foundation was winding down and JEMS was growing. We moved

our offices and our collective brood of kids to the San Diego

area. We were married in 1984.

Jane and I became good friends and

worked well together, although we resisted the temptation to get

romantically involved — until 1980, that is. By 1983, the

ACT Foundation was winding down and JEMS was growing. We moved

our offices and our collective brood of kids to the San Diego

area. We were married in 1984.

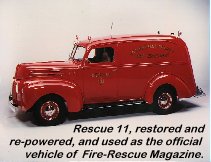

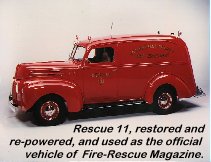

Most days since then, I have said,

"Life just doesn’t get any better than this." For

five years between ’84 and ’89, I returned to the fire

service, completing that career as the fire chief in Monterey

Park (where I started as a firefighter). Our home is in Carlsbad,

on a hill, with a view that stretches from Dana Point to La

Jolla. The only legal work I do these days is pro bono (free)

representation of paramedics who are being disciplined. In

’93, we sold Jems Communications to Mosby, a division of

Times Mirror. I have continued as publisher of both JEMS and

Fire-Rescue Magazine, a job that I love.

Most days since then, I have said,

"Life just doesn’t get any better than this." For

five years between ’84 and ’89, I returned to the fire

service, completing that career as the fire chief in Monterey

Park (where I started as a firefighter). Our home is in Carlsbad,

on a hill, with a view that stretches from Dana Point to La

Jolla. The only legal work I do these days is pro bono (free)

representation of paramedics who are being disciplined. In

’93, we sold Jems Communications to Mosby, a division of

Times Mirror. I have continued as publisher of both JEMS and

Fire-Rescue Magazine, a job that I love.

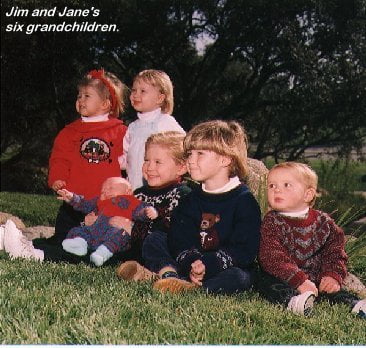

Our

merged family is very tight-knit. One of the girls, Deborah, is a

lawyer in nearby Vista. She and her husband have two sons.

Daughter Susan is an advertising sales manager in Seattle where

she also trains horses and her husband practices law. When the

whole bunch gets together - four kids and their spouses, and the

six grandkids - it is great fun.

Our

merged family is very tight-knit. One of the girls, Deborah, is a

lawyer in nearby Vista. She and her husband have two sons.

Daughter Susan is an advertising sales manager in Seattle where

she also trains horses and her husband practices law. When the

whole bunch gets together - four kids and their spouses, and the

six grandkids - it is great fun.

Thanks for this opportunity

to share my story with "Emergency!" fans. It’s

been fun going back over all those memories, even though some of

them were pretty painful. In the end, I don’t believe I will

ever again have the opportunity to participate in anything that

will have such a positive impact on so many people.

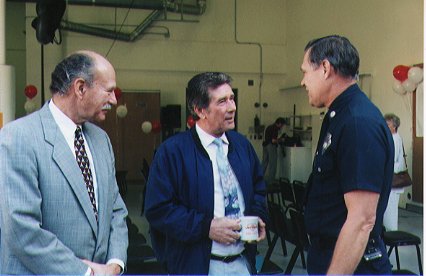

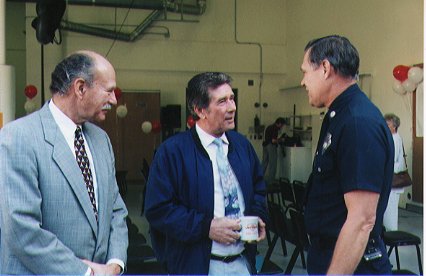

In November 1995, Universal Studios and the LA County Fire

Department jointly dedicated the new fire station on the studio grounds as

"Station 51." Attending the event were (left to right) Jim Page, Robert Fuller,

and Captain Roy Burleson, who once served as a paramedic technical advisor. (left)

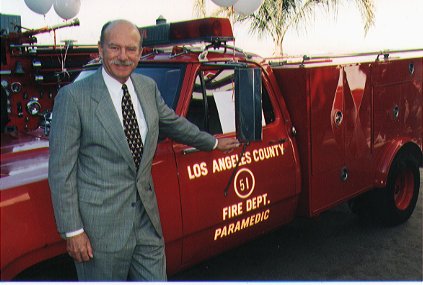

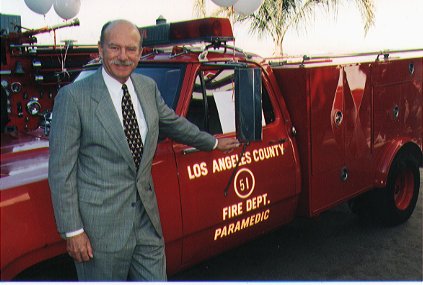

Jim Page posed for a photo with Squad 51 at the

dedication of the new Fire Station 51 at Universal Studio in

1995. (right)

Copyright 1998, James O.

Page

We'd like to thank Mr. Page for his tremendous contribution to

the page, his patience with all our questions, and loaning us his

pictures!

[Home] [People,

Places & Things]

Clearly, the favorite activity for my

tag-along guests was a trip to see "Emergency!" being

filmed, either on location or in a soundstage at Universal.

Clearly, the favorite activity for my

tag-along guests was a trip to see "Emergency!" being

filmed, either on location or in a soundstage at Universal.

Twenty-five years later, I still encounter

people - in places like Rochester, Phoenix, and Kalamazoo -- who

remind me of the day they visited us in Los Angeles and I took

them with me to the studio.

Twenty-five years later, I still encounter

people - in places like Rochester, Phoenix, and Kalamazoo -- who

remind me of the day they visited us in Los Angeles and I took

them with me to the studio. In February 1973, I moved into an apartment

next door to my law office in Covina. On weekends, I would try to

do something with my boys. Meanwhile, I had purchased a second

motorhome, a Condor, which I rented to Universal Studios. It was

used by Randy and Kevin when they were on location. When the

second season of "Emergency!" ended in the summer of

'73, there was a hiatus. I bought dirt bikes for Tom and Andy and

we took a vacation to Washington State in the Champion motorhome

(with the bikes trailered behind it).

In February 1973, I moved into an apartment

next door to my law office in Covina. On weekends, I would try to

do something with my boys. Meanwhile, I had purchased a second

motorhome, a Condor, which I rented to Universal Studios. It was

used by Randy and Kevin when they were on location. When the

second season of "Emergency!" ended in the summer of

'73, there was a hiatus. I bought dirt bikes for Tom and Andy and

we took a vacation to Washington State in the Champion motorhome

(with the bikes trailered behind it). As it turned out, the only physical

injury was a small scrape on the ankle of one of the girls. The

cause of the explosion was found to be two simultaneous defects.

The thermostat on the water heater failed to shut off the flame

when it reached 140 degrees F. It continued to heat the water

till it reached the boiling point (212 degrees). At that point, a

pop-off valve on the top of the hot water tank should have

released the steam but it failed too. As a result, the water tank

became a steam pressure vessel. When water turns to steam in a

sealed container, it expands about 1,100 to one, creating enough

power to move a locomotive — or demolish a motorhome.

As it turned out, the only physical

injury was a small scrape on the ankle of one of the girls. The

cause of the explosion was found to be two simultaneous defects.

The thermostat on the water heater failed to shut off the flame

when it reached 140 degrees F. It continued to heat the water

till it reached the boiling point (212 degrees). At that point, a

pop-off valve on the top of the hot water tank should have

released the steam but it failed too. As a result, the water tank

became a steam pressure vessel. When water turns to steam in a

sealed container, it expands about 1,100 to one, creating enough

power to move a locomotive — or demolish a motorhome. After making arrangements to get all

the kids home, and having the motorhome removed to a wrecking

yard in Yucca Valley, I had the rest of the weekend to think. I

thought about the tragedy that almost happened. I thought about

the way I’d been spending my life. I thought about all the

bridges I had burned and the anger (in myself and others) that I

was confronting every day. I realized that I was very unhappy and

that I probably wouldn’t be able to make things better in my

current situation.

After making arrangements to get all

the kids home, and having the motorhome removed to a wrecking

yard in Yucca Valley, I had the rest of the weekend to think. I

thought about the tragedy that almost happened. I thought about

the way I’d been spending my life. I thought about all the

bridges I had burned and the anger (in myself and others) that I

was confronting every day. I realized that I was very unhappy and

that I probably wouldn’t be able to make things better in my

current situation.  Tom graduated from Ithaca College in

New York with degrees in photography and cinematography. He has

been a commercial photographer in San Diego County for about ten

years. He is married with two children and lives in Vista,

California. Andy is a firefighter/paramedic in Poway (San Diego

area) and is working on his bachelors degree and studying for the

Captain’s exam on his days off. He is married with two kids

and lives in Temecula, California. Tom and Andy are both good

husbands and fathers — better than their Dad was — and

I’m very proud of them. Their mother (Pat) remarried and has

a lovely 22-year-old daughter who is attending UC Santa Barbara.

We include them in all our family get-togethers.

Tom graduated from Ithaca College in

New York with degrees in photography and cinematography. He has

been a commercial photographer in San Diego County for about ten

years. He is married with two children and lives in Vista,

California. Andy is a firefighter/paramedic in Poway (San Diego

area) and is working on his bachelors degree and studying for the

Captain’s exam on his days off. He is married with two kids

and lives in Temecula, California. Tom and Andy are both good

husbands and fathers — better than their Dad was — and

I’m very proud of them. Their mother (Pat) remarried and has

a lovely 22-year-old daughter who is attending UC Santa Barbara.

We include them in all our family get-togethers. My career took me to Basking Ridge,

New Jersey in 1976, as executive director of the non-profit ACT

(Advanced Coronary Treatment) Foundation. Funded by several

pharmaceutical companies, my job was to promote CPR training

nationwide and to provide technical assistance to communities in

upgrading their EMS to the paramedic level. It was the best job I

will ever have but our success — in promoting CPR and

upgrading EMS — ultimately would bring an end to the

Foundation. In anticipation of that event we created JEMS

(Journal of Emergency Medical Services) in 1980.

My career took me to Basking Ridge,

New Jersey in 1976, as executive director of the non-profit ACT

(Advanced Coronary Treatment) Foundation. Funded by several

pharmaceutical companies, my job was to promote CPR training

nationwide and to provide technical assistance to communities in

upgrading their EMS to the paramedic level. It was the best job I

will ever have but our success — in promoting CPR and

upgrading EMS — ultimately would bring an end to the

Foundation. In anticipation of that event we created JEMS

(Journal of Emergency Medical Services) in 1980. Jane and I became good friends and

worked well together, although we resisted the temptation to get

romantically involved — until 1980, that is. By 1983, the

ACT Foundation was winding down and JEMS was growing. We moved

our offices and our collective brood of kids to the San Diego

area. We were married in 1984.

Jane and I became good friends and

worked well together, although we resisted the temptation to get

romantically involved — until 1980, that is. By 1983, the

ACT Foundation was winding down and JEMS was growing. We moved

our offices and our collective brood of kids to the San Diego

area. We were married in 1984. Most days since then, I have said,

"Life just doesn’t get any better than this." For

five years between ’84 and ’89, I returned to the fire

service, completing that career as the fire chief in Monterey

Park (where I started as a firefighter). Our home is in Carlsbad,

on a hill, with a view that stretches from Dana Point to La

Jolla. The only legal work I do these days is pro bono (free)

representation of paramedics who are being disciplined. In

’93, we sold Jems Communications to Mosby, a division of

Times Mirror. I have continued as publisher of both JEMS and

Fire-Rescue Magazine, a job that I love.

Most days since then, I have said,

"Life just doesn’t get any better than this." For

five years between ’84 and ’89, I returned to the fire

service, completing that career as the fire chief in Monterey

Park (where I started as a firefighter). Our home is in Carlsbad,

on a hill, with a view that stretches from Dana Point to La

Jolla. The only legal work I do these days is pro bono (free)

representation of paramedics who are being disciplined. In

’93, we sold Jems Communications to Mosby, a division of

Times Mirror. I have continued as publisher of both JEMS and

Fire-Rescue Magazine, a job that I love. Our

merged family is very tight-knit. One of the girls, Deborah, is a

lawyer in nearby Vista. She and her husband have two sons.

Daughter Susan is an advertising sales manager in Seattle where

she also trains horses and her husband practices law. When the

whole bunch gets together - four kids and their spouses, and the

six grandkids - it is great fun.

Our

merged family is very tight-knit. One of the girls, Deborah, is a

lawyer in nearby Vista. She and her husband have two sons.

Daughter Susan is an advertising sales manager in Seattle where

she also trains horses and her husband practices law. When the

whole bunch gets together - four kids and their spouses, and the

six grandkids - it is great fun.