Chapter 3

More About

Topanga

Of course, Mike had movie-star

good looks. At the time, he was collecting royalties from an

underarm deodorant commercial he had appeared in (I believe the

royalties were two or three times his fire department salary that

year). He was single and living in an apartment building near

LAX. The building was occupied mostly by female flight

attendants.

Being young and a little

impetuous, Mike would come to work and talk about his off-duty

romantic adventures. We worked with a couple of grumpy old men

who listened intently to Mike's stories but badmouthed him behind

his back. It was clear to me that they were just jealous. What I

cared about was how well he did his job, and he did his job very

well.

Mike always looked sharp; he kept

his uniforms clean and neat and his grooming was impeccable. He

was very diligent about his patrol duties. Even on very hot days

he would spend most of the day on patrol. He kept good records

and worked well with property owners (especially the ladies) to

clean up fire hazards.

Mike and I also shared an interest

in cars. At one point while we worked together, he bought a

chopped and channeled, fenderless '34 Ford coupe. Later, he drove

an Italian deTomaso Pantera coupe. My interest in cars had taken

a back seat to education and I was driving a beat-up '57 VW, but

I looked forward to the day when I could get behind the wheel of

something special. Mike Stoker and I forged a friendship that

survives to this day, and I've always been pleased to see him

attain and enjoy extraordinary personal and financial success.

I could write a whole book about

my experiences in Topanga Canyon (including catching Mama Cass

swimming in the nude at Barry McGuire's house (you don't want to

hear about it), rescuing Tisha Sterling's horse (she's Ann

Sothern's daughter), and giving a ticket to Bob Denver (Gilligan)

for vandalism). Some of the most vivid memories, however, involve

rescues and brushfires. Topanga Canyon Boulevard twists and turns

through 12 miles between the San Fernando Valley and the Pacific

Ocean. In the summer, tens of thousands of cars traverse the

two-lane road going to and returning from the beach. Lots of them

crash and/or leave the road and careen to the bottom of the

canyon. Our job was to extricate people from those crashes

(before there was a "Jaws of Life") and package them

for transport in an ambulance.

Fire station 69 was the only

government facility in Topanga that was staffed 24 hours a day.

People would come there for first aid (bees stings, skinned

knees, broken toes, etc.), for advice on property purchases

("When was the last time a fire burned through that

area?"), and family matters (everything from a frustrated

mother wanting us to scold her delinquent son to a squabbling

newlywed couple who wanted us to settle their argument). In a

serious medical emergency, we were all that stood between life

and death in many cases -- and we were terribly limited in what

we could do. The following story was written a few years ago but

never published. It may offer some perspective on how things were

and why the advent of paramedics was so important.

"I was the Captain at

Fire Station 69, and we got a call reporting a woman with

breathing difficulty. A young firefighter and I jumped into a

patrol pickup truck - along with a Lyt-Port resuscitator and

a first aid kit - and raced up the canyon to the narrow,

winding road where the woman and her family lived. After

parking our rig, we scrambled up the 50 to 60 steps from the

roadway to the little house perched on the side of the

canyon.

"The woman was in her

thirties, she had a history of asthma, and she was struggling

valiantly to breathe when we got there. As my partner set up

the oxygen, I stepped to the phone and called our dispatcher.

It was a 20-minute response for the ambulance and I wanted to

make sure it was rolling.

"The woman's name was

Marjorie. At first, the oxygen seemed to help. But then she

lost consciousness, and her breaths became sporadic. My

partner and I were among the first people on the West Coast

trained in CPR, but we were both praying we wouldn't have to

use it on Marjorie. Over the sound of the oxygen flowing, and

the sound of her husband trying to calm their two little

girls, we strained our ears for the sound of an ambulance

siren coming up the canyon.

"In those days, we

weren't allowed to carry stethoscopes or blood pressure

cuffs. But our CPR training had taught us to check the

carotid pulse. When Marjorie's skin color began to change, I

felt for a pulse and it wasn't there. We started CPR about

the time we heard the ambulance coming up the canyon.

"The next several

minutes were a blur. There was no chance of getting the

gurney up those steps, or continuing CPR while going down the

steps. In a frantic scramble of arms and legs, we picked up

Marjorie and raced down the stairs with her to the ambulance.

It was almost a free fall, and every muscle of our bodies was

fighting to get down those stairs as fast as possible without

falling or dropping our patient. I don't remember doing it,

but somewhere during that downhill sprint, I twisted my ankle

so badly that I spent the next two weeks on crutches.

"In the ambulance, we

resumed CPR. Already, my lips felt swollen, and my partner

was sweating profusely as he did chest compressions and

shouted out a breathless cadence.

"The ambulance was an

International Travel-All with a V-8 engine and automatic

transmission. The driver had left the lights on and the

engine running - but the engine had died. I remember the

interior overhead lights dimming as the driver engaged the

starter. I remember the sickening sound of the engine turning

a slow revolution-and-a-half before it pulled the lights down

even dimmer.

"'One-and-two-and-three-and-four-and…,'

my partner was counting as the driver engaged the starter

again. Same result. About that time, I got my first taste of

another person's stomach secretions. We stopped CPR

momentarily, turned the patient on her side, and tried to

scoop the vomit out of her mouth. I remember shouting to the

ambulance crew that we had jumper cables in our truck.

"I remember how I felt

as I breathed into the woman's mouth again. A wave of nausea

surged from the pit of my stomach to the tip of my head. I

fought it back by concentrating on the fact that we were all

that stood between life and death for a young wife and

mother. The young firefighter offered to switch positions. I

turned him down, and then caught myself wishing I hadn't.

"Because of the narrow

road, the ambulance guys had to drive the patrol truck up the

road to a wide spot, turn it around, and bring it back

nose-to-nose with the ambulance. We continued CPR, and it

seemed an eternity before the driver got back in and engaged

the starter again. Same result. I guessed that the problem

was the starter, not the battery.

"You can probably

understand why I remember that awful night 25 years ago.

Another ambulance was dispatched - arrival time: 45 minutes.

A Deputy Sheriff arrived at the scene and sized it up pretty

quickly. He knew a physician who lived in the canyon. He went

to his home and then delivered the doctor to our location,

where he pronounced Marjorie dead. For the fifteen minutes or

so before the doctor pronounced her, we felt her skin

temperature turn from warm to cool to clammy.

"About five years

after that terrible night in Topanga Canyon, I found myself

in a classroom at Harbor General Hospital in L.A. I was a

chief officer by then, and some of my firefighters were

learning about wonderful new tools and procedures and

medications, and we were all learning how to use them. As I

held a defibrillator in my hands for the first time, I

thought about Marjorie. As I learned all about endotracheal

tubes and esophageal obturators, I thought about Marjorie's

desperate and losing battle to breathe. As I learned about

bronchodilators and other medications, I realized that with

the advances of those five years, we could have given that

young woman the opportunity to watch her daughters grow up.

"Marjorie's death

changed my life, and it shaped my career. I will never be

able to rest as long as people can die in North America for

the lack of quality emergency medical services."

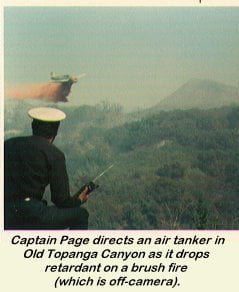

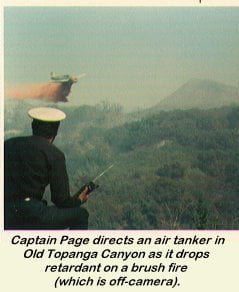

The book about my experiences in

Topanga, if it ever gets written, also will try to paint a word

picture of the phenomenon of California brush fires. There were

lots of little ones and a few big ones while I was stationed at

Topanga. On one occasion, I misjudged a situation and nearly lost

my entire crew. In 1994, I wrote about that incident in my

"Command Post" column for Rescue Magazine. It was

called "Surfing with the Devil":

"Watching TV reports

of the recent fires in Southern California produced a flood

of memories for me. Especially when a fire jumped a ridge on

the edge of the San Fernando Valley and raced through Topanga

Canyon toward the ocean.

"Twenty-four years

earlier, I was the fire captain on duty at Station 69 in

Topanga Canyon. The Santa Anas were blowing, and the air was

pungent with the fragrance of native vegetation as it

protects itself against the hot, dry winds. Our fire company

consisted of five people, a pumper and two small patrol

trucks.

"We all knew the

weather conditions were ripe for a fire, so early in the day

we deployed both patrol units. We roamed the public roads

throughout our 100-square mile area, making ourselves

visible, scaring off would-be arsonists and watching for

smoke.

"I was in Patrol 69

around noon when we received an alarm:

‘Brush fire reported

in Woodland Hills north of Topanga Canyon Boulevard.’

"Looking in that

direction, I saw the header, flipped on the lights and siren,

and headed toward it. Engine 69 was responding from the

station and Patrol 269 was en-route from Old Topanga Canyon.

"As I wrestled the

small truck through the road's twists and turns, I was

thinking of the advice of old-timers who had fought a

half-dozen fires in the same terrain. The only way to keep a

fire out of Topanga is to stop it at the ridge that separates

Woodland Hills from the canyon, they had said. But nobody had

ever been able to stop a wind-driven fire at the ridge. I

wanted to be the first.

"Every year, fire

department bulldozers clear a fuel break along the ridge, and

a dirt fire road passes through the middle of the cleared

area. I pulled the patrol truck onto the fire road and drove

a quarter-mile to a saddle where I could look down on the

fire. The wind had died down, and the smoke was rising

straight up.

"A few minutes later,

Engine 69 arrived on scene. 'We've got a chance of stopping

this thing here at the ridge,' I explained to the crew. 'If

the wind doesn't pick up.'

"My plan was to

backfire from the ridge toward the fire. That way, when the

fire made its run to the top, it would run out of fuel before

gaining the momentum necessary to cross the fuel break.

"We spaced ourselves

about a hundred yards apart and began lighting backfires. The

brush burned eagerly and the backfires began to grow

together.

"Just then, the hot

wind picked up and started to blow in gusts of 50 mph or

more. About the same time, the heat from the main fire and

our backfires merged to produce a kind of flashover.

"Spontaneously, we

started running for our vehicles -- but we couldn't run fast

enough. I had the sensation of being inside the curl of a

giant ocean wave. But the substance of that curl was hot

beyond description and filled with biting smoke and red-hot

embers.

"It was like surfing

in hell.

"As we ran, it was

impossible to see or breathe. The embers were like a swarm of

angry bees, finding their way into gloves, boots, collars and

pant legs. By the time we arrived at our pumper, which had an

open cab, the engine had died for lack of oxygen. We all

rushed to the patrol truck and crowded into the cab. Before I

could close the vent-wing, a thousand hot embers blew in

after us.

"In two or three

minutes, the worst was over, and we reemerged into the smoke

and embers to extinguish fires that had started in the

pumper's upholstery, hosebed and storage bins. At the same

time, I reported to incoming units that the fire had slopped

over the ridge and was heading into Topanga Canyon.

"Two days later, the

fire was contained -- after the weather changed and moist

ocean air replaced the Santa Anas. During those two days, my

thoughts were dominated by remorse. In the quest for personal

achievement, I had placed my crew in a position of

unacceptable risk.

"In the years

following that fire, the brush grew back, as it has for tens

of thousands of years. And now it has burned again, as it

must in order to propagate.

"The most to be gained

from that frightening episode is a lesson I am compelled to

share with others who are entrusted with the lives and

welfare of emergency services personnel.

"In pursuit of a

personal challenge, I placed my crew in jeopardy. They

survived and forgave me, but I have never forgiven myself.

The brush grew back, but dead firefighters and rescuers

cannot be replaced. Regardless of our emergency service

environment, let that be a lesson to all of us."

Hello

Hollywood

In 1969, after moving my family

off the ranch, I started getting the itch for some "flatland

experience" (in LA County FD, that refers to a station that

is not in "the stumps", the hilly or mountainous areas

where brush fires occur). I put in a bid for Station 7 in West

Hollywood. The transfer occurred in January, 1970. Thus began a

series of events that would drastically change my life and

career.

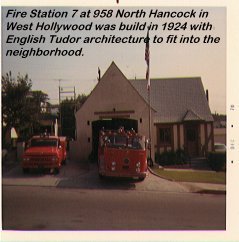

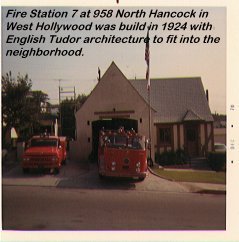

Then and now, Station 7 was the oldest

building used by the County Fire Department as a fire station (It

was built in 1924, which may not seem old in other parts of the

country. But, in Southern California, that meant the

non-reinforced masonry construction of the building had survived

numerous earthquakes. All other fire stations from that era had

been replaced with more modern, earthquake-resistant structures).

Station 7's architecture was English Tudor and it was intended to

blend in with the neighboring residences on Hancock Street. I

loved the place and it will always be my favorite fire station.

Then and now, Station 7 was the oldest

building used by the County Fire Department as a fire station (It

was built in 1924, which may not seem old in other parts of the

country. But, in Southern California, that meant the

non-reinforced masonry construction of the building had survived

numerous earthquakes. All other fire stations from that era had

been replaced with more modern, earthquake-resistant structures).

Station 7's architecture was English Tudor and it was intended to

blend in with the neighboring residences on Hancock Street. I

loved the place and it will always be my favorite fire station.

Station 7 housed an engine and a

rescue squad (Engine and Squad 7) with a six-person crew. The

rescue squad was still operating at the first-aid level. That

included the administration of oxygen, splinting, and bandaging,

but no cardiac defibrillation, no taking EKGs or administering

drugs, and no insertion of adjunctive airways. We were not

allowed to carry stethoscopes and only about half of our people

had been trained in the new technique of CPR.

What’s

a "Paramedic"?

About that time, we had heard

about and read about (in department memos and "Straight

Streams," the monthly magazine published by the

Firefighters' Benefit and Welfare Assn.) the "Rescue Heart

Unit" that was being implemented in Battalion 7. Previously,

we had read about a new program in the Miami Fire Department

wherein a number of firefighters had been trained to be

"paramedics." In that Florida program, according to an

article in Fire Engineering Magazine, the specially trained

firefighters could do some sophisticated medical procedures that

previously only physicians were allowed to do.

When I first read the article

about the Miami "paramedic" program, I was fascinated

by it. It caused me to think of all the people whose lives had

slipped through my fingers over the years. There was so little we

could do for them. The new concept of "paramedics" was

promising but I doubted that our department would take such a

bold step. Then I heard about the "Rescue Heart Unit"

program.

The Miami program actually had

been inspired by the work of Dr. J. Frank Pantridge of Belfast,

Northern Ireland. He had created a mobile coronary care unit at

the Royal Victoria Hospital and, over a period of a year or two,

demonstrated that lives could be saved by taking emergency

coronary care to the patient, rather than waiting for the patient

to arrive at the hospital. He was

invited to the U.S. to report on

his project at a meeting of the American College of Cardiology

(ACC).

Attending the ACC meeting were Dr.

Eugene Nagel of Miami, Dr. William Grace of New York, Dr. Leonard

Cobb of Seattle, Dr. James Warren of Columbus, Ohio, and Drs.

Walter Graf (of Daniel Freeman Hospital) and J. Michael Criley

(of Harbor General Hospital) from Los Angeles, among others.

Shortly thereafter, all of these cardiologists were putting

together programs in their respective cities to try to achieve

what Dr. Pantridge had in Belfast. Dr. Nagel, in Miami, was first

to get his program up and running. In the Los Angeles area, Drs.

Graf and Criley actually were constructing competing models. It

was Criley's project that would hit the streets of L.A. first.

At the fire station level, we knew

little of this background, except for the limited information

that was reported in fire service and departmental publications.

At about the time I transferred to Station 7, the first six L.A.

County firefighter/paramedics were completing their didactic

training and clinical rotations at Harbor General. Those six were

Bob Belliveau, Dale Cauble, Gerry Nolls, Gary Davis, Bob

Ramstead, and Roscoe ("Rocky") Doke, as I recall. It

was time for them to take their skills to the street, but then

someone pointed out that there was no law that would permit them

to operate in the field without direct supervision.

Copyright 1998,

James O. Page

CHAPTER 4

Then and now, Station 7 was the oldest

building used by the County Fire Department as a fire station (It

was built in 1924, which may not seem old in other parts of the

country. But, in Southern California, that meant the

non-reinforced masonry construction of the building had survived

numerous earthquakes. All other fire stations from that era had

been replaced with more modern, earthquake-resistant structures).

Station 7's architecture was English Tudor and it was intended to

blend in with the neighboring residences on Hancock Street. I

loved the place and it will always be my favorite fire station.

Then and now, Station 7 was the oldest

building used by the County Fire Department as a fire station (It

was built in 1924, which may not seem old in other parts of the

country. But, in Southern California, that meant the

non-reinforced masonry construction of the building had survived

numerous earthquakes. All other fire stations from that era had

been replaced with more modern, earthquake-resistant structures).

Station 7's architecture was English Tudor and it was intended to

blend in with the neighboring residences on Hancock Street. I

loved the place and it will always be my favorite fire station.